Having spent 24 years of his life in the United States since childhood, Madsaki relocated to Tokyo in 2004, starting his career from scratch. Today, he stands as one of the Tokyo’s most iconic artists. His journey—creating something original out of nothing—embodies the very concept of Nothingness.

In this interview, we gained exclusive access to Madsaki’s Tokyo-based studio, the core of his creative practice. We spoke with him about the evolution of his work, the ideas behind it, and why he continues to call Tokyo home.

You moved from New York to Japan in 2004, but were you already thinking about pursuing art in Tokyo at the time?

Not really. I wasn’t as serious about art back then. I was more like—just going with the flow. I already knew it wasn’t going to be easy making a living through art. You know I was working as a bike messenger in New York, right? At the time in Japan, when people thought of bikes, it was mostly road bikes—guys in those tight spandex outfits. But I was riding this weird fixed gear bike in Dickies, and people were like, “Wait, can you ride like that?” and “What, no brakes?”

That fixed gear scene ended up kicking off a whole boom in Japan, right? And soon after, you were suddenly hanging out with people like Hiroshi Fujiwara, Jun Takahashi (Undercover), and Yoppi—basically all the icons that everyone in Tokyo street culture wanted to meet at the time.

Yeah, I think it was just rare to meet someone who had lived in the U.S. that long, so people were kind of curious about me. Honestly, I didn’t even know who they were when people first introduced me. Later people would be like, “You know that person’s a big deal, right?” and I’d just go, “Oh, really?” Maybe that actually helped, though. I had no preconceived notions—so I just talked to them as people, without any idea of what they did or how famous they were. So before anything art-related, I actually got media attention for that.

I’m guessing you were surrounded by some intense characters back in New York too. Did you feel any difference compared to the key figures you met in Tokyo?

Nah, man—messengers were like the cockroaches of the city. [laughs] Even in New York, I never met the stylish crowd, like the Supreme people or whatever—they weren’t on my radar, and I didn’t care either. I was really in the raw, underground scene. So honestly, I couldn’t even tell you what the difference was. I didn’t have that kind of perspective.

In 2005, you even collaborated on a piece with Jun Takahashi. That’s a pretty major development right after coming back to Japan. How did you first meet Jun?

Someone invited me to a fashion show in Ebisu, like, “Hey, let’s go check this out.” I didn’t know anything about Undercover, or who Jonio was at the time. But I got introduced to him there. He asked, “What do you do?” and I said, “I ride bikes and paint.” And he was like, “You should stop by my office sometime.”

So it felt like you clicked right away when you first met?

Yeah, totally. When I went to his office, he was like, “Wanna do something together?” and I was like, “Sure, let’s do it.” So we just started painting together and ended up showing the work. It all just kind of flowed, you know? It happened really naturally.

Your style shifted a bit after that. In your collaboration with Adidas, for example, you used simple lines to explore space and even worked on massive sculptural pieces.

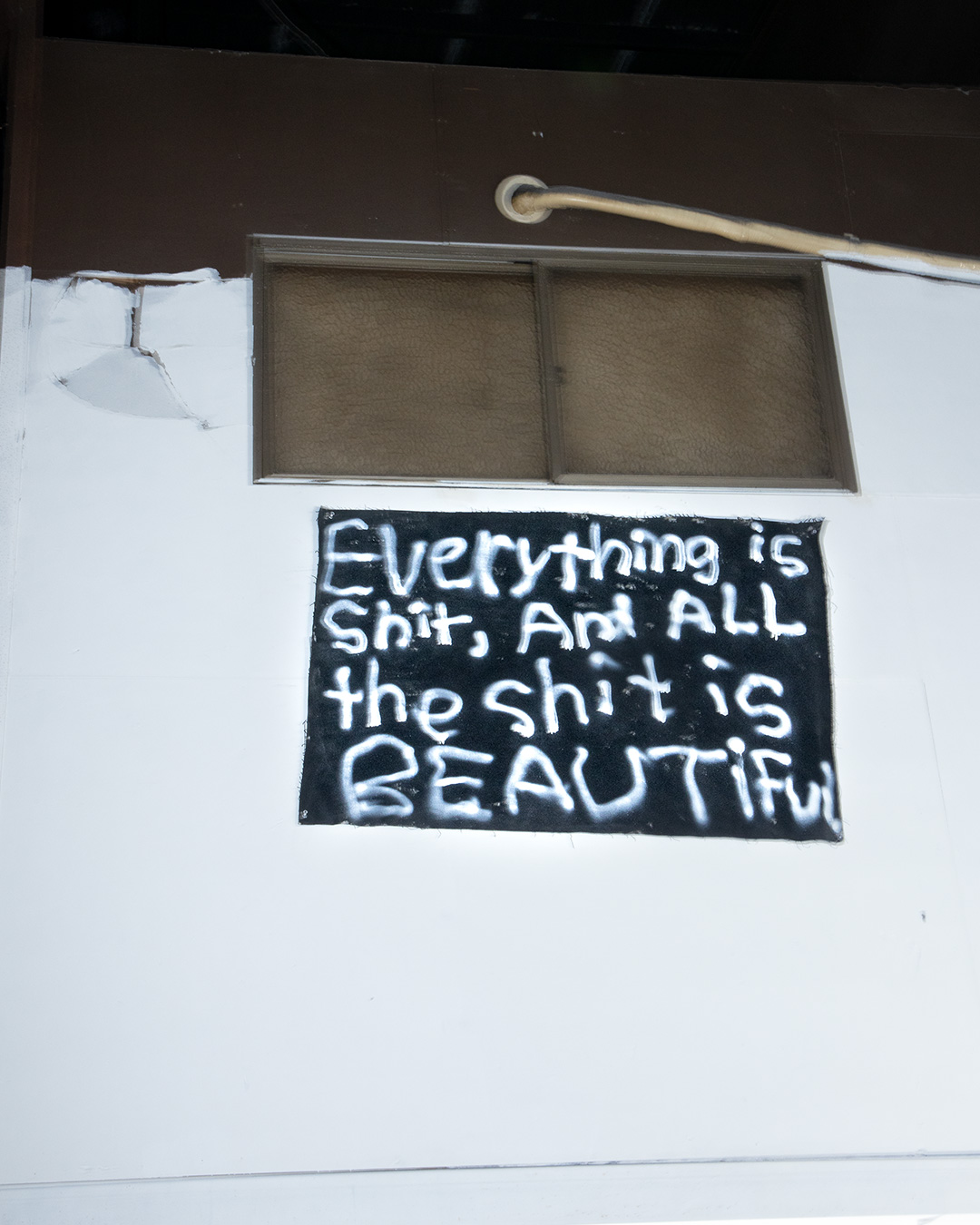

Yeah, I tend to change my style a lot. For me, painting is about expressing whatever’s going on inside at that moment. My whole thing is that not having a style is my style. Once you lock yourself into a certain style, it’s like putting yourself in a box—it starts to feel stiff and boring. I mean, everyone eats and eventually takes a shit, right? [laughs] Painting, to me, is about constantly outputting, and through that, learning more about yourself. Even if what you’re putting out sometimes sucks, you just keep going—you keep putting out shapeless shit. That’s still the process I’m in today.

Around 2013, your style shifted again—you started creating word-based works, almost like scrawled emotional outbursts. (“Write Here, Write Now” at Clear Edition & Gallery.) What was that period like for you?

That was rock bottom for me, financially. I was 40 at the time, had a family, and I was doing night shifts at the Setagaya post office just to get by. I didn’t even feel like painting then, so I started working with words instead. The curator at Clear Edition & Gallery said, “Why don’t you try painting these?” So I started spray-painting the text. I remember thinking—if this doesn’t work, maybe I should just get a regular job.

But you know, art… I don’t think you need to go through hell to make good work, but when I look at art by people who haven’t struggled, it just feels shallow. That period was really tough, but in some strange way, I was also enjoying it. Looking back now, I think that struggle was actually a good thing for me.

Even during those hard times, it sounds like a part of you was still enjoying it.

Of course. If I wasn’t enjoying it, I wouldn’t have kept making art. I mean, art isn’t something the world needs, right? [laughs] And from there, my style evolved into the one with the characters crying ink from their eyes—what became the “Wannabie’s Collection” at Clear Edition & Gallery in 2016.

Your work was featured in Takashi Murakami’s Superflat Collection exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art in 2016. That seemed to mark the beginning of your connection with him—how did that come about?

Man, that really surprised me too. Turns out Takashi—well, I always call him Takashi-san—had come to see my “Wannabie’s” solo show. Later, he DM’d me on Instagram asking if he could buy one of my works. It was a piece inspired by Matisse’s Dance, and I sold it to him.

Since I always wrote in English on Instagram, he thought I was a foreigner at first—so the message came in English! [laughs] But I had no idea he was going to include the piece in the Superflat Collection show. A friend told me it was there, so I just showed up to the opening—even though I wasn’t invited. [laughs]

What was your impression of Murakami back then?

Actually, back when I was working as a messenger in New York, I once saw Takashi-san walking down Broadway. Of course, I already knew who he was—even then. I mean, I’d never heard of a Japanese artist who had broken into the Western art world like that. I had a lot of respect for him.

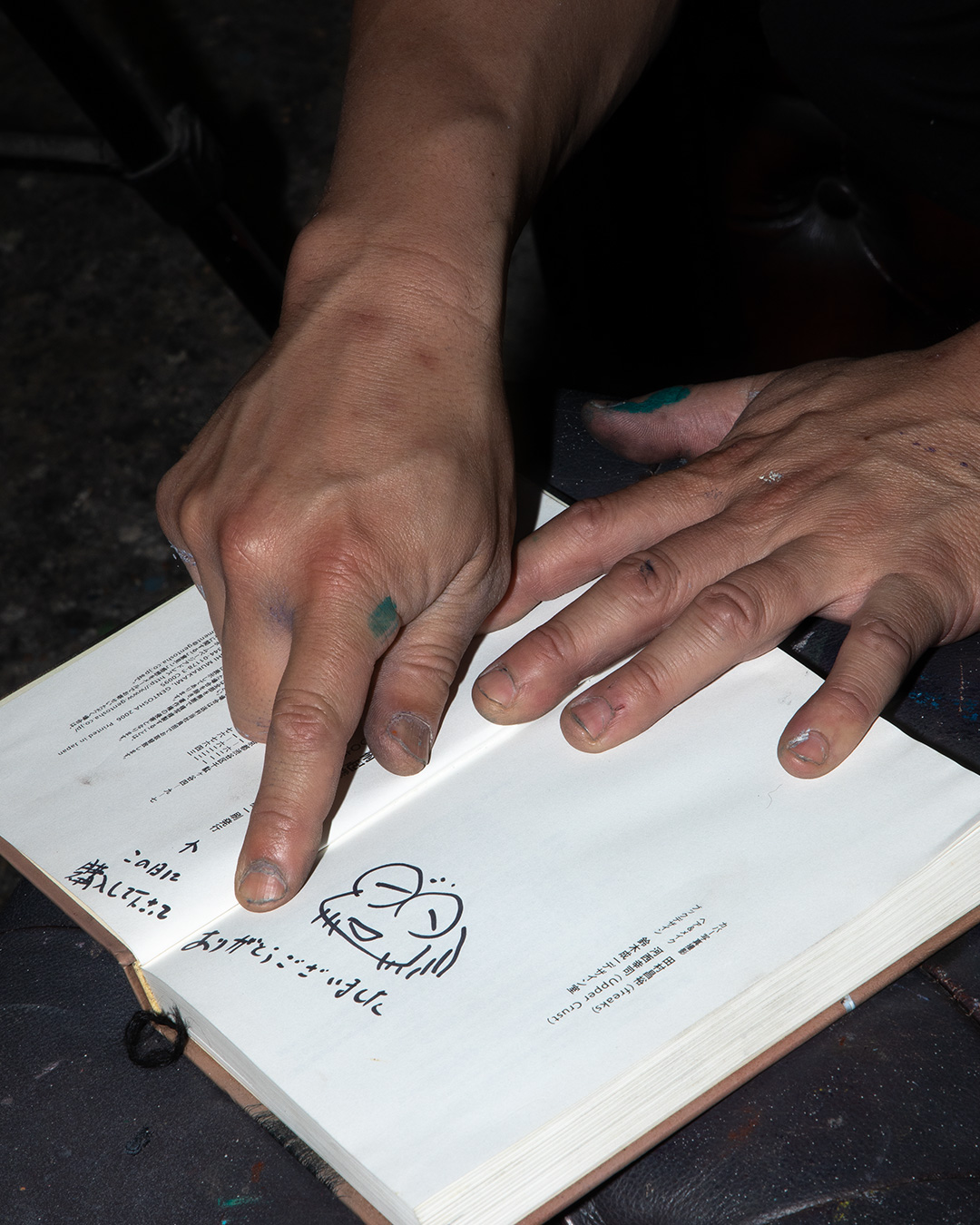

His book Art Entrepreneurship Theory (Geijutsu Kigyouron) was released on June 25, 2006—and I literally went to Aoyama Book Center to buy it on the day it dropped. I did graduate from an art school in the U.S., so I’d been thoroughly schooled on how the art world really works. It’s not the romanticized version most people imagine—it’s a full-on business. So everything he wrote in that book just made perfect sense to me. It all clicked.

Much later, here at this studio, I asked him to sign my copy. He wrote: “Thank you for purchasing this on release day.” [laughs]

So when you got that DM from Murakami himself saying he wanted to buy your work…

I was honestly blown away. That moment made me feel like everything I’d done up to that point had been worth it—especially since I was at rock bottom back then.

That’s why I went to the Yokohama Museum opening, even though I wasn’t invited. It was the first time I actually got to say hi to him. The piece he bought was one of my Matisse-inspired “Wannabies,” so when I introduced myself I said, “I’m Matisse!” [laughs] And he replied, “Oh, so you’re Matisse!” We even took a photo together in front of the piece.

Then he told me, “I’m opening a new space in Nakano, you should come by,” so I went to that opening too.

And that eventually led to you joining Kaikai Kiki Gallery.

Yeah, but it didn’t happen overnight. At that Nakano opening, Takashi-san asked me, “Can you do a solo show at Hidari Zingaro in two or three months?” I said, “Absolutely.” I knew it was a test.

That solo show—“Hickory Dickory Dock” in 2016—actually sold really well, and I think even he was surprised. After that, I had a show at Kaikai Kiki Gallery—“Here Today, Gone Tomorrow,” also in 2016—and we even painted together a few times.

Then one morning he called me in and asked, “How many pieces can you make in a year? You’ll need to do at least 80.” I said, “No problem. I can do it.”

From there, he helped connect me with Perrotin Gallery, and we eventually signed the contract—that’s how I officially joined Kaikai Kiki Gallery.

Around this time, you also started working on large-scale canvas pieces, and your name began gaining global recognition. How did that feel for you?

Looking back, it really felt like I was in the right place at the right time. My name blew up pretty fast—and honestly, the art market is a whole different scene now. It was a good moment to be in. I got in at the right time.

In 2023, you held your solo exhibition This Used to Be My Playground at Kaikai Kiki Gallery, focusing on your personal experiences in Tokyo’s nightlife. That show marked a major shift—you moved away from the “ink dripping from the eyes” style and started painting eyes again.

Yeah, that club series wasn’t originally meant to be shown to the public. After years of doing the “Wannabies” and the ink-dripping eyes—even at Kaikai Kiki—I had started feeling burnt out on it. So I began painting these just for myself, privately, with no intention of showing them.

Some of the pieces even featured specific people—like Kun (Kunichi Nomura) or Virgil (Abloh)—and I figured stuff like that wouldn’t really land in the art world. But then one day, Takashi-san came by the studio, saw the works, and said, “You need to show this.” That’s how the exhibition ended up happening.

One striking thing about that show wasn’t just that the characters had eyes again—it was also the first time “Tokyo” appeared so clearly in your work.

That actually started with Kun saying to me, “Masaki, why don’t you ever paint Tokyo when you live here?” I told him, “I don’t feel like I belong in Tokyo. There’s nothing I want to paint.” And he goes, “Dude, you’re always at Mild Bunch.” [laughs] That’s when it hit me.

He said, “Tokyo’s nightlife is beautiful too. And besides, you only come out at night anyway.” I was like—yeah, he’s right.

Did you really feel like you didn’t have a place in Tokyo before that?

Yeah. I mean, up until then, I was always thinking in English and translating it into Japanese when I spoke. That caused a lot of misunderstandings—like, people here would say, “You’re too much,” or “Your words are too strong.” I think I came off as intense to some Japanese people.

But Kun and the Mild Bunch crew accepted me just the way I am. That was the only place in Tokyo where I felt like I truly belonged.

It wasn’t until I started painting that series that I thought, “You know what, I actually really like Tokyo.” For the first time, I felt like—I’m really here. I’m in Tokyo.

So it took almost 20 years to really feel that way.

Yeah, it really took 20 years. [laughs] But I think Tokyo changed a lot during that time too. Back in the day, people felt more surface-level to me. But things started shifting—like when Takashi-san did that collaboration with Louis Vuitton. That moment kind of marked a turning point.

I remember thinking, “Okay, that old, superficial Tokyo is gone now.” And that’s when things started getting interesting for me. Little by little, I realized—Tokyo isn’t an away game for me anymore. It’s home now.

And what’s your impression of New York now?

It’s a great place to visit—but I wouldn’t want to live there anymore. Maybe I sound like an old guy saying this, but the New York I lived in was just better. Now it’s like… the whole world has turned into a Starbucks. [laughs]

Back when I was there, the U.S. economy wasn’t doing great, and that’s what made it interesting. I think the same applies to Japan now—part of what makes it exciting is that the economy’s kind of messed up. Culture always seems to thrive when things are unstable.

When I look at young people in Japan today, they’re not really looking up to America anymore. From my perspective, doing something uniquely Japanese in Japan—that feels fresh now.

And yeah, the weak yen is probably part of it too, but people from all over the world seem drawn to Japan right now because it looks like something interesting is happening here.

Honestly, if I were living in New York today, I don’t think I’d be making art. I’d probably be too comfortable with my surroundings. But in Tokyo, in a good way, I’m not satisfied. I don’t have anything else I want to do besides paint, so I just keep creating.

What does “living as an artist in Tokyo” mean to you personally?

Japan isn’t exactly the easiest place for art to grow, so being able to make a living as a real working artist here—I’m proud of that.

There are people like Takashi-san who’ve paved the way, but he’s kind of like the Rolling Stones at this point. [laughs] Still, I want to carve out my own path too—something that makes it a little easier for the next generation to walk behind me.

Making a living through art is hard, not just in Japan but anywhere. But this is what I really want to do. And if I want it that badly, I’ve got no choice but to prove that it can be done—even here in Tokyo.

Lately on Instagram, you’ve been posting what almost feel like handwritten diary entries in English. Sometimes they’re about your creative process, other times they touch on more personal struggles. A lot of people seem to find it surprising—and maybe even comforting—that an artist as big as you still shares those emotions. What’s the intention behind those posts?

Well, I’m over 50 now. It’s not like I’m trying to do some kind of social service, but I do feel this urge to pass on what I’ve learned—to share it in a way that’s easy to understand for the younger generation.

In my case, the words only work because the paintings come first. But sometimes, there are things that can’t be fully expressed through images alone. Words can make it clearer. And judging by the reactions, it seems like it’s hitting people—it’s something they’ve been looking for.

Instagram is full of people only showing the “good stuff,” right? So I’m like, fine—I’ll show you my shit too! [laughs] I guess this is my way of giving something back, after everything I’ve been given.

You’ve mentioned that you spend a lot of time in this studio. What do you feel this space connects you to?

To me, this place is a portal. It’s this remote spot I found seven or eight years ago—totally off the grid. No one really comes here, and I actually like being alone, so I spend most of my time here when I’m working.

From here, I can connect to other dimensions. And the works I create here—they go out into the world, even if I don’t.

MADSAKI @madsaki

Artist. Born in Osaka in 1974, Madsaki moved to New Jersey in 1980. He graduated from the Parsons School of Design (Fine Arts) in 1996. While working as a bicycle messenger in New York, he continued to create art, eventually returning to Japan in 2004. His bold spray works explore themes rooted in a complex identity shaped by life in both Japan and the U.S. He has held solo exhibitions not only in Japan but also internationally.