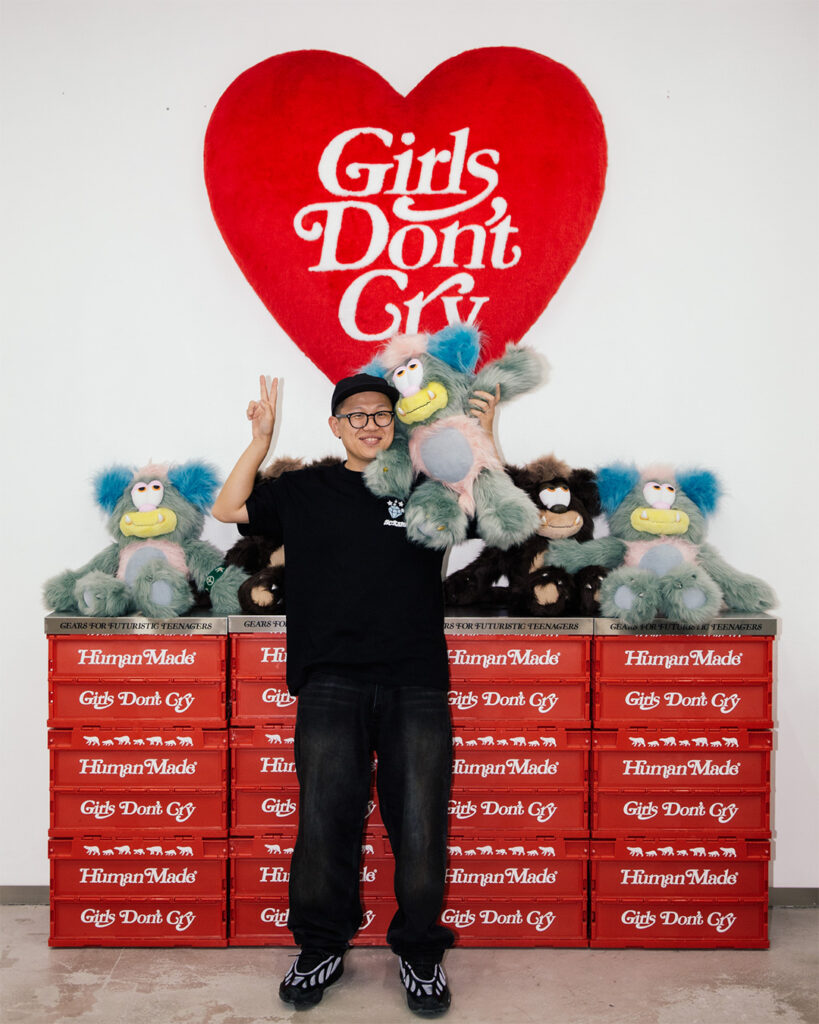

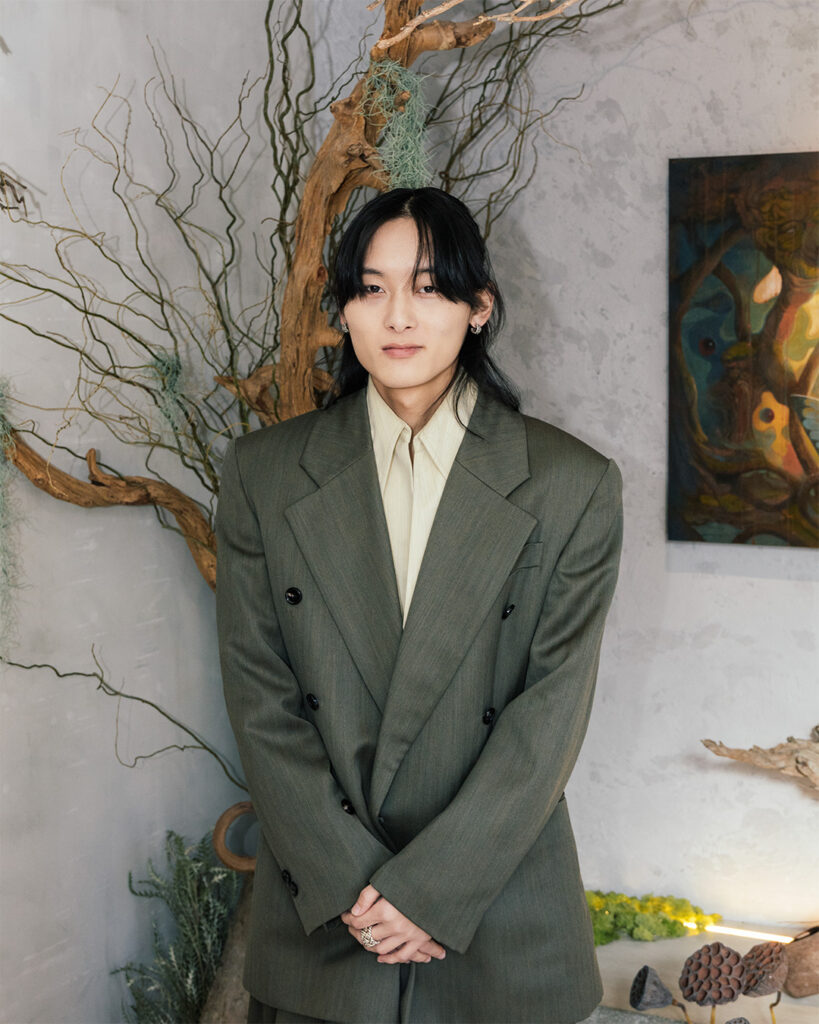

Among the rising generation of Japanese designers, one of the brightest names is Shinpei Goto of Masu (pronounced M-A-S-U). In 2018, at just 25 years old, Goto took over as lead designer for the brand, and within just a few short years, he claimed the Grand Prix at the Fashion Prize of Tokyo 2024. He has also shown twice at Paris Men’s Fashion Week—a significant milestone for any young designer.

Born in the 1990s, Goto is a true member of Generation Z, and while his creations have found a particularly strong following among his peers, their appeal cuts across generational and gender lines, resonating with a much broader audience.

You became the designer for Masu in 2018, at the young age of just 25. What was your mindset at the time?

It all came about through a chance connection around the time I decided to leave my previous company. It wasn’t a large company, but they already had the infrastructure to produce apparel, which I saw as a real opportunity. That said, I made it clear from the start that I wouldn’t just be continuing what the previous designer had been doing.

Your previous job was at Laila, a company known for vintage apparel, right?

Yes, I was involved with the launch of a men’s brand at Laila. It started with remaking jeans, which gradually developed into a full-fledged brand. It was the kind of environment where no one really taught you what to do—everyone was basically figuring things out as they went.

So, I ended up doing everything—from sketching designs and planning collections to choosing fabrics and trims. I also handled production management, delivery, and sales. I was involved in every stage of the process, which, for someone 24 or 25, made me a pretty “cost-effective” employee.

If I had only been doing design work, the company would have needed to hire separate people to handle production management and other tasks, which would have meant more overhead. I think one of the main reasons I got the offer to join this company was that I already had a wide enough skill set to handle a lot of those roles myself.

I imagine the brand still carried the image and identity established by the previous designer. Did you ever feel like, “If that’s the case, I’d rather just start something from scratch”?

To be honest, I did feel that way. But at the end of the day, it wasn’t something I owned, and it was a brand that had been created with its own story and vision. So, I decided to respect that and carry it forward.

What kind of direction did you envision for the new Masu under your leadership?

At my core, I’m the type of person who likes to dig deep into a narrow focus. But I figured that kind of depth would probably come more naturally as I got older, once I’d gained more experience. So, with this brand, I wanted to challenge myself to see how far I could push strong, creative ideas on a broader scale. That’s been my approach from the very beginning, and it hasn’t changed since.

So, you were also thinking about producing in larger quantities to some extent, right?

Yes, but my goal was to see how broadly I could spread pieces that, while technically mass-produced, still carried the spirit and quality of one-of-a-kind creations. In a way, it’s a challenging balance to strike.

When your version of Masu started, luxury streetwear was still dominant globally, so I imagine your approach—creating something new based on vintage elements—really helped the brand stand out. Around the same time, it seems like people your age were also starting to get excited about vintage and Americana. Were you aware of those trends as they were emerging?

Honestly, I was just doing what I liked and what I knew how to do. In the early days, I was intentionally making things that I knew wouldn’t necessarily be popular. That was during the peak of designers like Gosha Rubchinskiy and Demna, when the whole mood was very different—there was no real space for antiques or vintage influences.

But I made a conscious effort not to bend to that. I knew what the mainstream was, but if I’d just gone with the flow from the start, I felt like I’d end up continuing to deceiving myself.

Among Japanese designers of your generation, brands like Dairiku and Kamiya, along with Masu, have been gaining attention for their creations rooted in vintage and Americana influences.

Yeah, I do feel like we share some overlapping tastes. Our generation definitely appreciates vintage, but I think we also tend to look at it with a more neutral, less reverential eye—for better or worse. It’s not just about old automatically meaning good, or getting hung up on details like selvedge edges. It’s a more intuitive approach.

Of course, if you don’t understand the history and just try to replicate it without context, that comes off as lame. But I think there’s a certain freedom in the way our generation approaches it.

What is it about vintage and Amekaji that draws you in personally?

There are lots of things I find appealing, but one big part is the freedom to define a piece’s value yourself. There’s also the thrill of finding one-of-a-kind pieces and the surprises that come with that.

For me, clothing as a whole is a form of communication. In that sense, I think vintage can be a kind of universal language that transcends generations—a tool for conversation.

The vintage boom isn’t just a Japanese trend—it’s a global one now. How do you feel about this situation? It seems like things have gotten a bit overhyped, especially in terms of pricing.

I think it’s a good thing that vintage is becoming more popular, and it definitely benefits my brand. But I do feel a bit uncomfortable with the way it’s spreading in some circles, where the focus is more on added value and rarity than the actual essence of the piece. Of course, everyone can decide for themselves what that “essence” is, but I feel like vintage should be appreciated in a more straightforward, less hierarchical way.

Also, I just don’t like that it’s gotten so expensive—it’s made it harder for me to shop for myself.

Masu’s clothing also reflects a sensibility that’s a bit different from Amekaji vintage, doesn’t it?

I think that partly comes from my earliest memories of playing with my grandmother’s clothes as a kid. Because they were hers, they were women’s clothes, but I remember my brother and I would drape them around ourselves or wrap them around our necks and pretend we were gangsters. We’d just play freely in her closet, and that sense of excitement and imagination really stuck with me.

I believe that kind of thrill isn’t limited by age or gender, and it’s something I want to keep pursuing with the brand.

Also, I think I was a bit influenced by my older brother’s old copies of Men’s Egg, the gyaru-o* fashion magazine. I’ve actually been hunting down old issues on Mercari recently (laughs).

*Gyaru-o – The male counterpart to the gyaru subculture, popular in the early 2000s. Known for deep tans, heavily styled hair, flashy branded clothing, and a mix of surfer, host, and biker influences. Magazines like Men’s Egg helped define the look and lifestyle.

Men’s Egg was a hugely popular magazine in the early 2000s. Looking back, it feels like it represented a kind of street culture that existed separately from the mainstream fashion scene.

Yeah, it really was an interesting culture, and I still find myself looking back at it for inspiration. The whole bosozoku (motorcycle gang) influence is something you can still see in both Japanese and international fashion, but the gyaru-o culture—guys who dressed in that ultra-flashy style—is still kind of under the radar for people outside Japan. That’s actually a uniquely Japanese thing.

And, of course, I have to say Kimutaku (Takuya Kimura) was always cool, even back then. For my generation, he’s always the symbol of what it means to be cool.

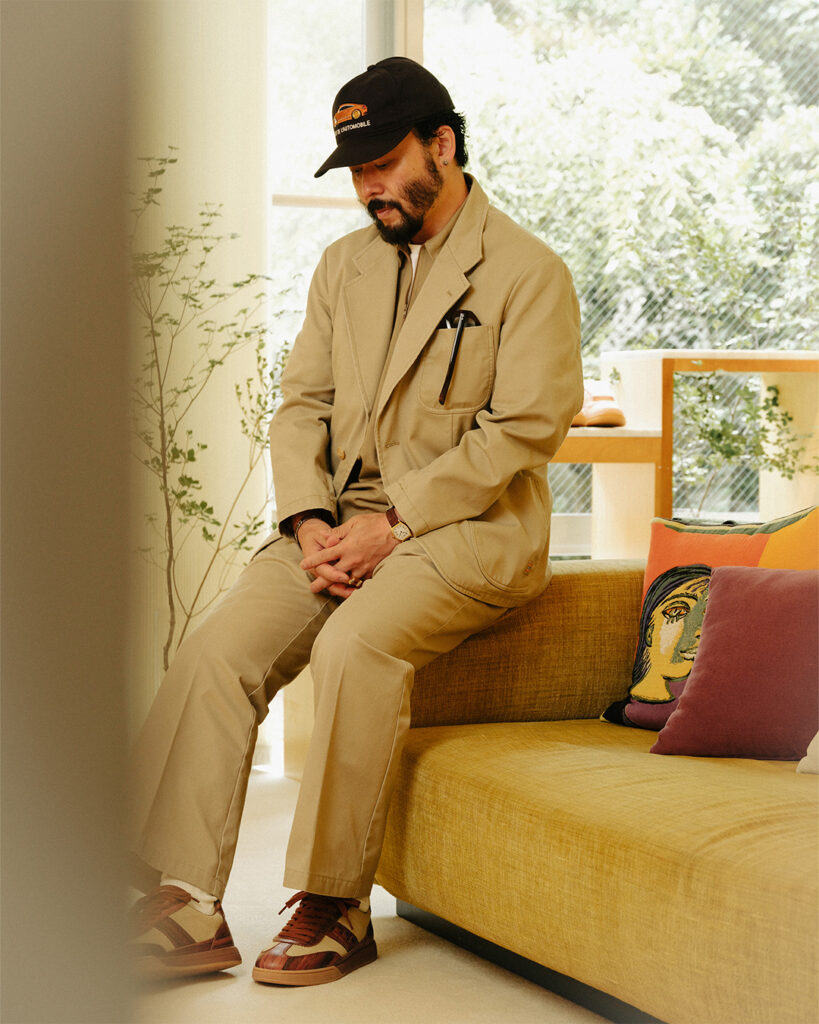

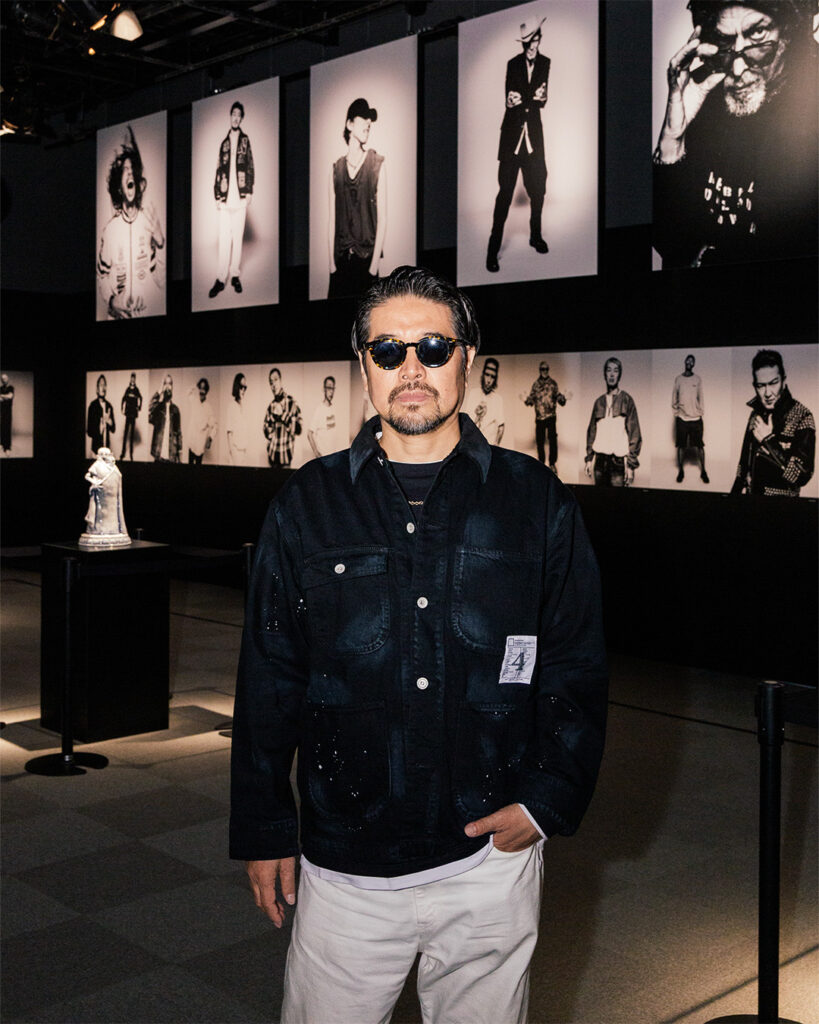

Masu has gained a strong following among Gen Z, but it’s also resonated with older generations who have been deeply involved in fashion for years, like Poggy. How do you interpret this broad appeal?

One factor is that vintage serves as a kind of common language across generations. But another major influence is my time at Laila. Laila probably has the world’s largest collection of Maison Martin Margiela, and it also carries pieces by Helmut Lang, Raf Simons, Saint Laurent, Hermès, Pierre Cardin, and even Eastwest—a truly special mix of vintage fashion.

When I was a student, I worked at Laila doing repairs on those kinds of garments, and being able to handle and study them up close taught me a lot.

What was it about handling those pieces that left such a strong impression on you?

It depends on the brand, but I’d say it’s the way every detail is so thoroughly thought out. Some pieces are designed to look effortless or rough, but when you really examine them, you realize that nothing is actually left to chance—every single element has a purpose.

It’s not just the fabric or the silhouette, but even down to the choice of buttons and the color of the stitching—nothing is overlooked. I realized early on that it’s those kinds of pieces that really stand the test of time.

And those experiences influenced your current creative approach.

I think those experiences helped me raise my standards and sharpen my eye. Even now, I want to create pieces that can stand alongside those truly special vintage items without feeling out of place.

I try to carry forward the sense of persuasiveness and quality I learned from those pieces, and maybe that’s why people from older generations can also relate to what I’m doing.

You won the Grand Prix at the Fashion Prize of Tokyo 2024 and have now shown at Paris Men’s Fashion Week. Has presenting in Paris changed your perspective at all?

I have to admit, for better or worse, I realized that Paris really is the pinnacle. The sheer number of people observing is on the scale of something like the Olympics or the World Cup, so I understand why everyone flocks there.

At the same time, though, I also felt like it’s a little too much “for France” or “for the big maisons.”

I see. What made you feel that way?

Given how expensive everything is in France these days, it feels like we’re all going there to earn money, but end up sinking enough into the trip to build an entire house.

It also started to feel like smaller brands like mine are just setting the stage for the big maisons to shine. We could keep playing that game, but I’m not sure that’s the best path for Japanese fashion as a whole. Ideally, it should be the other way around—people from overseas coming to Japan for our fashion week or our own shows. That’s something I’ve felt for a while, but actually participating in Paris made me feel it even more strongly.

Another thing that surprised me was when some European buyers said, “I can’t tell if this is men’s or women’s clothing—I want you to make the distinction clearer.”

That’s a bit surprising.

Yeah, it is, right? But I think there are probably a lot more people in Europe who think that way than we might expect. In Japan, fashion is a bit more fluid—no one really bats an eye if a guy wears a skirt, or if I show up in something flashy like what I’m wearing today. That kind of openness might still be something that’s only a “standard” here in Japan.

Fashion can be deeply personal, and sometimes people make assumptions about a designer’s identity based on the style of clothing they create. Do you ever find that people make those kinds of assumptions about you?

I feel like that kind of thinking actually limits the possibilities of fashion. If more people around the world could appreciate fashion as freely and neutrally as people in Japan, I think it would really broaden the horizon for everyone.

You skipped the runway for your 2025AW collection in Paris, right? What are your plans for the next season?

Yeah, I did two shows, but for 2025AW I decided to present the collection as a lookbook instead. I’m thinking of doing the same for 2026SS.

On the flip side, I’m starting to feel like I want to do something interesting in Japan instead. Doing a collection for Paris every season just doesn’t quite feel right for me. I feel like I should be pursuing a different path—something that only I can express.

I don’t have a concrete answer yet, but that’s the direction I’m leaning.

There are a lot of brands now exploring ways to present collections without being tied to the traditional seasonal cycle, right?

Yeah, and I get it—there’s a certain inevitability to it—but the way fashion operates now feels like it’s become too much of a “money-making machine.” The whole cycle of putting out collections every six months just to keep the cash flowing strikes me as a bit off.

It’s become totally normal for brands to expect people to wear completely different looks from head to toe every season, but I think that’s strange. I still wear clothes from last year, and even pieces from ten years ago.

The fashion industry tries to act like it’s okay with that, but deep down, I feel like the entire structure is still built on rejecting that kind of longevity.

That’s a tricky balance, though. Having deadlines is part of what drives new creations, too.

It’s true that having deadlines helps you focus, but I’m a bit skeptical about that, too. I sometimes wonder if, without those deadlines, we might be able to create something truly groundbreaking—like an “iPhone of clothing.”

You mean clothing that can be constantly updated on the inside? I have no idea what that would look like, but it sounds fascinating.

Yeah, like a kind of masterpiece—something designed with the assumption that everyone will own it. I find myself daydreaming about that kind of thing lately. I feel like I want to do something experimental like that.

Fashion as a concept is still relatively young, and I feel like we’re approaching a moment where it’s ready for a fundamental shift.

MASU @masu_officialaccount

SHINPEI GOTO @shinpei.goto

Born in 1992 in Aichi, Japan. He graduated from the menswear design course at Bunka Fashion College in 2014. After graduation, he joined Laila, a company specializing in vintage pieces from maison brands, where he was involved in planning and production as a founding member of its in-house brand. Since the fall/winter 2018 season, he has served as the designer of Masu and received the grand prize at Fashion Prize of Tokyo 2024.