Proleta Re Art hasn’t just arrived—it’s hacked its way into the spotlight, rewriting the rules in their ascendancy. The brainchild of designer and craftsman Prot and embroidery artist Eri, this duo transforms denim garments into one-of-a-kind art objects through meticulous, almost obsessive reworking. As the word “art” in their name suggests, each piece they produce is more than just clothing—it’s a wearable sculpture, embodying their belief that fashion can transcend utility and become something deeply expressive.

In direct opposition to mass production and fast fashion, they dedicate themselves to one customer, one garment at a time—pouring their hard-won skills into every stitch. To wear Proleta Re Art is to wear a piece of their soul. Having launched their brand only a few years ago with nothing more than an Instagram post, they’ve quickly captured international attention. In fact, since Yuta Hosokawa’s Readymade and Saint Mxxxxxx (Saint Michael) emerged in the late 2010s, no other Japanese label has sparked a global buzz quite like they have.

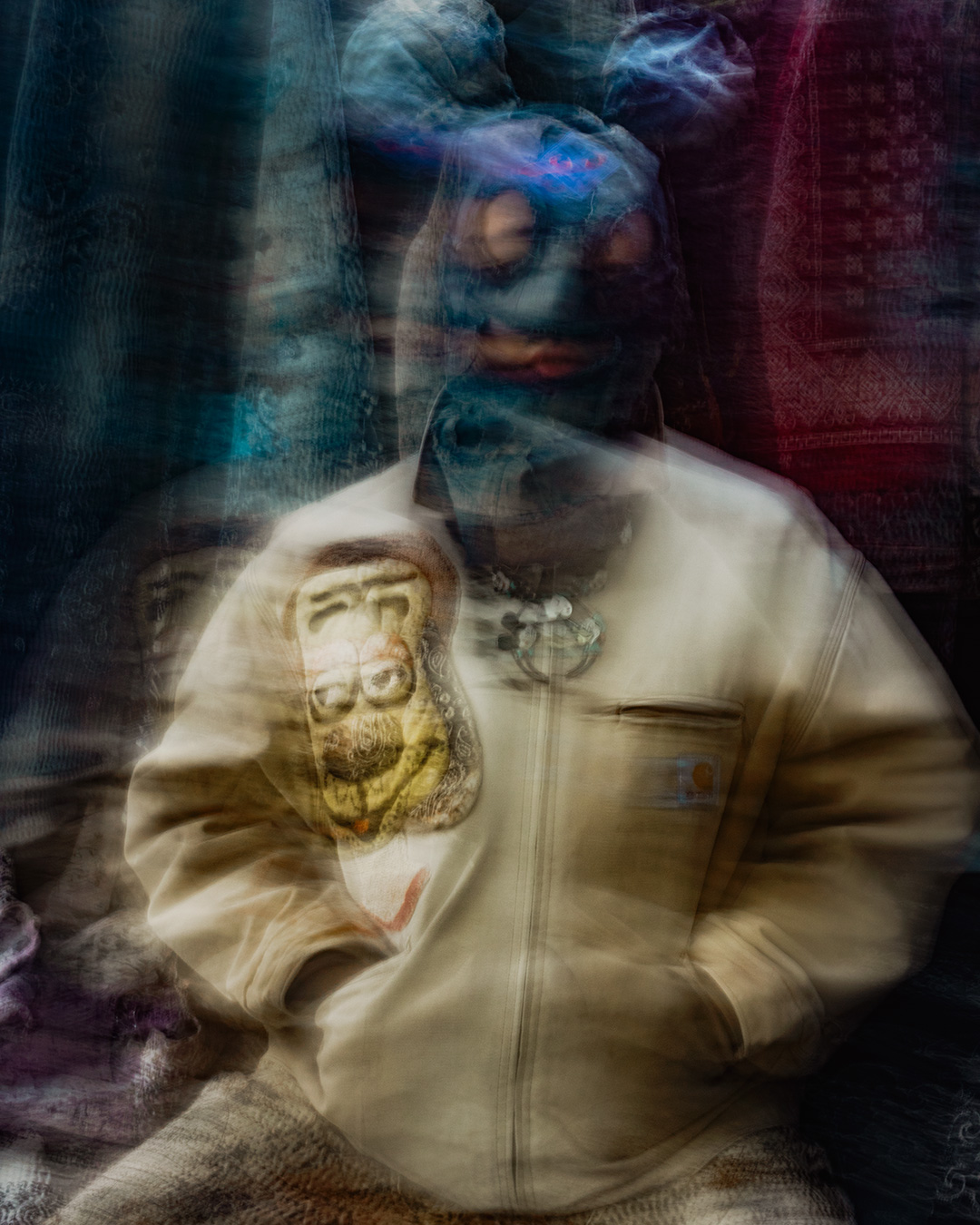

From world-class rappers to elite athletes, Proleta Re Art has captivated fashion insiders with their radical approach. We sat down with Prot to talk about their origin story, the philosophy behind their so-called “hacking” process, and why they choose to do things entirely their own way.

Tell us how the brand started—and where the name comes from.

We officially launched Proleta Re Art in 2021. Before that, I’d spent about ten years working as a designer for a brand in Okayama that specialized in vintage denim processing and remakes. But at some point, due to a mix of circumstances, I had to leave the company in 2020 for health reasons.

Eri, who I now work with, was a colleague back then—she was in a different department, but many of my designs would go through her team in the production phase. Even during our time at that company, we were working with deadstock items and B-grade garments—things that couldn’t be sold as new because of fading from exposure to shop display lighting or other minor flaws. Our job was to rework and add value to these items through specialist techniques. So after we both left, it felt natural to continue along that path. We started sourcing vintage pieces and slowly began selling custom-repaired and reworked garments on our own.

From an upcycling standpoint, vintage makes a great base material—and thanks to online platforms like Mercari and Yahoo! Auctions, you don’t need a big corporate infrastructure to get started anymore. It’s all accessible.

Also, Eri comes from a family that used to run a classic Ivy-style select shop, going all the way back to her grandfather. They’re no longer in business, but her grandfather and father were serious collectors of brands like Van Jacket, so we’d often get pieces from their archives. If they weren’t our size, we’d repurpose the fabric and use them as materials in our own work.

Eri left the company first, and I followed shortly after. We moved to Tokyo together from Okayama, but at the time, I hardly knew anyone in the fashion industry here, and no stores were willing to carry our work. So I thought, “Why not just try selling on Yahoo! Auctions?” I’d actually used the platform since high school—buying and selling vintage clothes—so I already had some experience. And I knew from watching auctions over the years that a lot of serious collectors used the site. I figured: if I list one-of-a-kind custom garments there, the right people might take notice.

There were already some “handmade creators” on Yahoo! Auctions and Mercari selling drawstring pouches or dresses made from indigo-dyed antique fabrics—but no one seemed to be offering pieces with the kind of intense, research-driven vintage processing we were doing. That’s exactly why I felt there was space—and value—in trying something new.

So I’d take, say, a vintage Levi’s trucker jacket, customize it, and list it under a title like Vintage Levi’s Trucker Jacket BORO Custom. I never wrote “this is a custom made by me”—I just listed the measurements and started the bidding at 1,000 yen. That way, anyone could jump in. And the response was amazing. I think people with a sharp eye for vintage saw the design and thought, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.” Some pieces sold for 10,000 yen, some for 50,000, even up to 400,000 yen—each time was different, but every piece sold. That was a big moment for me—realizing that something I made could actually bring in money was exhilarating.

We rented a run-down, leaky old house in the shitamachi (old downtown) area of Tokyo and made three or four pieces a week. Every Sunday, we’d list them. And when the previous week’s items got picked up, we’d post the next round. Sundays became our favorite day—Eri and I would sit in front of the screen together, wondering how much each piece would fetch. Over six months to a year, I think we made about a hundred pieces that way.

At that point, I hadn’t yet officially launched under the name Proleta Re Art, but seeing the comment “Where can I buy this?” made me respond in English: “I made this jacket—DM me if you’re interested.” To my surprise, traffic to my account shot up. I figured, why not share some photos of past pieces I’d listed on Yahoo! Auctions? So, I began posting them on my Instagram. My follower count—mostly made up of people I knew—was around 200 at the time, but before long, it started growing exponentially.

As more and more purchase inquiries came in, I started to feel that maybe I didn’t need to sell anonymously to the general public on Yahoo! Auctions anymore. Maybe I could actually create pieces for the people who genuinely wanted them. That realization pushed me to take the next step: to give the project a proper name, attach woven labels, and begin producing pieces under a brand identity.

In fact, ever since I left my previous job, I’d been thinking about what kind of concept and name I’d want if I ever launched a brand of my own. The name Proleta Re Art is built around the idea of giving new life to worn-out workwear—transforming it into art through repair and customization. It’s a kind of reincarnation.

The word comes from proletariat—the German term for the working class under capitalism. I reworked the “RIAT” ending: “ri” becomes “re” for recycle, and “at” becomes “art.” So the name expresses our concept of “re-arting” labor-worn garments—Proleta Re Art.

But there’s also a personal layer to it. Around the time I left my job and my health was failing, I found myself listening to Proletariat, an album by Japanese rapper Primal, on repeat. The way it wrestled with the tension of holding down a job while trying to pursue music—and the introspective way he faced himself—really struck a chord. I’d be listening to it in tears. The theme of Proletariat and my own emotional state at the time overlapped in a powerful way, and that resonance played a big part in why I chose this name.

For a while, I continued selling on Yahoo! Auctions in parallel, but as orders started steadily coming in through Instagram, I eventually stopped using the auction site altogether.

These days, I’ve shifted to a production style that focuses on made-to-order pieces—whether it’s for individual clients or boutiques.

So looking back, it seems like the attention really started overseas from the beginning. I imagine there were a few turning points along the way—but after your earlier pieces started gaining traction, who was the first well-known figure to place an order?

Actually, the earliest response came from outside Japan—especially the U.S. Not long after my work started getting some buzz, I began receiving orders from major names like A$AP Rocky, Lil Baby, 21 Savage, Travis Scott, and OBJ (Odell Beckham Jr.). They picked up and wore my pieces surprisingly early on, and from there, things really took off.

I think the very first to wear something was A$AP Bari. That happened just about three months after we’d officially started the brand as Proleta Re Art.

So right from the start, it was almost like a reverse import—your work gaining traction first in the American hip-hop and street scene.

Yes, to be honest, we still have very few clients in Japan. We get a steady stream of inquiries, but because each piece we make is so labor-intensive and entirely one-of-a-kind, the price inevitably ends up being high for a garment. As a result, most of the actual orders we receive tend to come from clients overseas—particularly those with the means to afford that kind of work.

Right, I have yet to spot anyone wearing one of your items just walking around Tokyo. Moving on, what does a typical day look like for you as a designer?

I usually wake up around 9 a.m.—some days I have breakfast, some days I don’t. I start working around 10. During the day, it’s usually me, my partner Eri, one full-time staff member, and another staffer who comes in two or three times a week—so we’re typically a team of four. The others usually head home around 8 or 9 p.m., but I’ll often keep working into the night. I usually take a bath and eat dinner after midnight, then go to sleep around 3 a.m. That’s pretty much my daily rhythm.

Since my atelier and living space are one and the same, unless I’m invited out to an event or dinner, my life is pretty much just eating, sleeping, and making things—a full-on hikikomori (reclusive) lifestyle, to be honest. People sometimes ask, “If you’re that focused on production, wouldn’t it be better to live somewhere cheaper than Tokyo?” But being based here makes it easy for people to come to the studio for meetings or interviews. Since I rarely go out myself, I think having a space where others can come to me is really important.

As for our production setup, aside from sourcing some materials and making patterns, we don’t outsource anything. We do everything ourselves. While I handle the design and vintage processing—things that require a specific vision or technique—when it comes to deconstructing vintage garments, cutting fabric, or sewing, our staff are often better at those steps than I am. Everyone brings different strengths to the table, and we divide the work accordingly.

Most of the time, we’re all heads down, totally focused on what we’re doing. So on days like today, when someone visits and we actually get to talk, it’s a rare—and refreshing—change of pace.

Are you still working primarily with vintage garments?

Some pieces are made using vintage as the base, while others are constructed entirely from scratch—it really depends on the item and the design. I always try to incorporate at least some worn material into each piece, but I don’t believe everything needs to be made from old fabric. What matters most to me is the vintage processing—the treatment itself.

Even if I’m working with brand-new materials, the techniques I use can artificially accelerate the passage of time, creating the kind of patina, depth, and character that normally takes years to develop. And when I do use fabric that would otherwise be considered unusable—like something torn or too damaged to sell—I’ll layer on repairs and distressing in a way that enhances the intensity, transforming it into something even more valuable than it was to begin with. That’s the approach I call hacking.

Among vintage purists, there are still people who look down on processed garments and dismiss them as fake. These days, vintage-style treatments are more accepted, even popular—but when I first started doing this kind of work, I’d get comments like, “It’s not real vintage, is it?” The implication was that it was somehow inauthentic or artificial.

That kind of thinking never sat right with me. Just because something is old doesn’t automatically make it superior. Wearing head-to-toe vintage doesn’t necessarily mean someone has great taste. I’ve always believed that fashion should be more free and open.

What drew me to my previous job in the first place was that they had a whole department focused on vintage processing and remakes. I remember falling in love with one of their one-off pieces and asking the shop staff, “Is this vintage?” They said, “Actually, it’s new. One craftsman handled everything—design, construction, and finishing.” That completely blew me away. I thought to myself, “It’s just incredible that something with this much depth and texture can be created by the hands of one person.”

The pieces had a level of quality that made it nearly impossible to tell whether they were vintage or newly made—and yet the designs were unlike anything you’d ever see in actual vintage. That’s where I saw real potential.

Even back when I was selling on Yahoo! Auctions, I deliberately chose not to write “This is a custom piece made by me” in the listings. In a sense, I wanted to outwit the vintage obsessives—to throw them off in a good way. It was never about deceiving anyone. I just didn’t want people to buy something because it was “a rare model from the mid-twentieth century” or “a low-run piece with historical value.”

I wanted my pieces to speak to the people who looked at them, and make them think, “This is absolutely insane,” purely by how they looked and how they made people feel—not based on status, rarity, or insider knowledge. I wanted our pieces to be purchased by people who truly felt something towards them.

Can you explain the concept of “Hacking”?

What I call “hacking” is actually inspired by hack ROM culture—a subculture where people with coding skills modify the ROM data of old games like Famicom (NES) or Super Famicom (SNES) titles, essentially creating entirely new versions of classic games. Hardcore fans with obsessive levels of love and skill take legendary games like Mega Man or Mario and transform them—ramping up the difficulty far beyond the original, changing the graphics, rewriting the music— a radical transformation by applying a kind of mad science.

As someone who had thoroughly played the original versions of those classic games, that kind of drastic remixing was incredibly exciting, and I saw a strong connection to what I do with vintage processing.

At the same time, it’s also a kind of rebuttal to people who dismiss processed garments as inferior to “real” vintage. There’s definitely an intentional element of misdirection—I want to trip up the so-called connoisseurs who pride themselves on their eye. For example, when I’m doing patchwork, I’ll intentionally mix genuine vintage fabric with newer fabric that’s been processed—so even seasoned collectors can’t tell which is which.

To me, hacking isn’t just a technique—it’s my philosophy for expression and an act of rebellion.

What’s the most important thing to you when it comes to making things?

Since I’m accepting money from clients in exchange for these pieces, quality is absolutely non-negotiable. And when I say quality, I don’t mean using expensive fabrics from prestigious mills or anything like that. I’m talking about the visual quality—the sheer beauty of the finished piece—and pushing that to the limit.

If there’s even the slightest imbalance, even just a millimeter off, I’ll take the entire piece apart, sew it again from scratch, then reprocess it so the correction blends in. Wash it, wear it in—it’s a whole cycle. And I do this with every single piece.

With a typical fashion brand, the process is divided: designer → pattern maker → sample maker → production manager → factory → inspection → retail. But for us, we handle every step ourselves. I’m not just the designer—I’m also the production manager, the craftsman, the accountant, the shipping department, the admin, and the business owner.

There’s not a single piece we’ve ever released that I wasn’t fully satisfied with. I take full responsibility for everything that goes out into the world, and that mindset is something I never intend to change.

Lately, I’ve seen some counterfeit versions of our pieces in circulation. But I can tell, just by looking at a photo, whether I made it or not. Every item we produce is numbered, and whether that number hits 1,000 or 3,000, I’m confident I could still identify each one with my own eyes.

People often ask, “Wouldn’t it be easier to just focus on design?” But I feel that handling everything myself—from the first sketch, to the financials, to the final shipment—is what guarantees I can take full responsibility for every single piece.

You’ve already touched on where the brand draws its overall inspiration—but when it comes to designing the clothes themselves, what kinds of things influence you?

It really varies. Sometimes it’s vintage clothing that sparks something, but other times it’s completely unrelated—like a graphic of some random character, a painting by an artist I admire, or even the atmosphere of a crumbling old office building I happen to stumble across.

Back when I was a student, I loved backpacking and spent a lot of time traveling through various countries across Asia. In those places, you’d often see bootleg signs on food stalls with drawings of Mickey Mouse or Dragon Ball characters. They were clearly drawn by amateurs—not particularly well at that—and maybe they only had access to a limited range of paint colors, so the hues were kind of off. But after being exposed to rain and wind, the red would fade to this sunburnt pink, and somehow it gave the whole thing this incredible character.

Of course, I think works by famous artists can be beautiful, too. But I’ve always been drawn to the things made by unknown people with no money—like hand-painted signs, or beat-up old workwear. Objects that are weathered, used-up, and full of quiet melancholy. That kind of imagery and texture is something I’ve always wanted to carry into my designs. If there’s one through-line, it’s that I’m rarely interested in clean, polished, brand-new-looking things. I’m much more inspired by the strange, the flawed, the things that have developed flavor over time. That’s where the magic tends to be for me.

How long does it typically take to make one piece?

It really depends on the design, so it’s hard to give a fixed number. But the most time-consuming piece I’ve made so far probably took around 200 hours. Even if everything goes smoothly and there’s no need to redo anything, each piece still takes about 15 hours to complete. And that’s just the physical labor—if you include the time spent developing the design concept, the total can be several times that.

There are plenty of times during production when I’ll stop and think, “Actually, this would look better if I did it another way,” and make changes on the fly. Other times, I’ll get halfway through something and realize it just doesn’t look good—so I’ll tear it all apart and start over from scratch. When that happens, the schedule gets pushed back significantly.

The kind of distressing and vintage processing I do is physically demanding, and many of the steps are hard to undo once they’re done. So yes, the work takes a lot of time. And there are definitely moments when I’ve missed deadlines—I always feel terrible for making my clients wait.

But I also know that if I were to rush something just to hit a deadline—cutting corners or leaving some tiny inconsistency untouched—it would ruin the whole piece. Worse, it would let the client down. That’s why I do my best to explain the situation clearly and ask for understanding when timing becomes an issue.

What’s the process like when delivering pieces to boutiques?

I always sit down with the store’s buyer and have a proper conversation to work out the design together. Since everything is a one-of-a-kind custom piece, it’s not just me saying, “Here’s what I want to make.” Whether it’s a buyer or a private client, I try to understand their preferences and current mood, and reflect that in the final piece—filtered through my own aesthetic. That’s part of what makes Proleta Re Art so distinctive.

The reason I stick with this approach is because I truly believe that when someone feels “This was made just for me,” they’ll value it more. It becomes something they’re less likely to let go of.

Even when I get an order through Instagram DMs, I’ll take a look at the client’s account and try to get a feel for what they like, what kind of life they live. If I can pick up on that vibe, then even while I’m making the piece, I find myself naturally thinking about them—adjusting little details with that person in mind.

Taking a shared sense of “this feels right” that emerges from dialogue with the client, and translating that into a finished form through my own lens—that’s the essence of my creative process.

It sounds like each piece is almost like a collaboration. Is there one you feel especially attached to?

I’m attached to all of them, really—but now and then, I receive special commissions for pieces meant to mark a meaningful occasion. One example is when A$AP Rocky and Rihanna had their first child—they asked me to create a baby blanket. They loved it so much that when their second child was born, they reached out again to request the same design in a different color.

To have world-class artists like them—who must receive endless gifts and clothing from all over the world—choose to commission something from us for such a personal moment… it was an incredible honor.

Later on, I got to see a photo of their child wrapped in the blanket, and it had this wonderfully worn-in look to it—way more battered than when I first made it, but in a good way. It meant so much to know that it wasn’t just sitting there as a keepsake—they were really using it in everyday life.

I also sometimes hear from people who bought my pieces back in the Yahoo! Auctions days, before Proleta Re Art officially existed. They’ll say things like, “I’m proud to own one of your earliest works—before there were even serial numbers.” Or, “I’ve been following you since the auction days, and it’s amazing to see how far the brand has come.” I’m genuinely grateful to all those early supporters. Their encouragement from the very beginning still means a lot to me.

What are your hopes or plans for the future?

I don’t have any goals like “I want to hit X in revenue within Y number of years.” I have zero desire to live a luxurious life, or to be seen a certain way, or to be admired. The only thing I really care about is how beautifully and precisely I can finish the piece in front of me.

If I tried to increase production volume just for the sake of growth, I’d lose the ability to take full responsibility for each individual piece. That said, I now have a team of people who support the work I do, and as someone running a business, I have a responsibility to help sustain their livelihoods. So yes, we do need to earn a certain amount to keep going. But rather than chasing quantity, I want to focus on building more depth into each piece and increasing its value—and then, wherever possible, I want to reinvest those earnings back into the team.

To make that possible, I know I need to invest in the right tools and environment. Right now, we’re working without any of the specialized equipment you’d find in a large-scale factory—everything is self-built, DIY. Honestly, it’s a stretch. So even if it’s just a small space, I’d love to have a workshop outfitted with the minimum professional equipment required to maintain our quality standards—while still keeping an eye on every piece that leaves the studio.

And another thing is that, if possible, I would like to have a showroom where we can show samples in person. We’re never going to mass-produce inventory for sale, but I’d love to go beyond just trading DMs and photos—ideally, we’d have a physical space where people could see the work up close and talk with us directly. Our clients often say, “The actual piece looks way crazier than the photos,” and that’s exactly why I think it would be amazing to create a setting where people can hold the work in their hands before placing an order.

PROLETA RE ART @proletareart